It is a strange irony that just when, after years of the “clash of systems” between East and West, Western democracy had claimed the field, discontent with it broke out and has been swelling up to the present day (for example: Crouch 2008; Geiselberger 2017; Hentges 2020). The Peace Report for 2020 speaks of a “worrying trend toward de-democratization” worldwide (BICC/HSFK/IFSH 2021). From external perspectives on Europe and the USA as well as with regard to the foreign policy of the West, Western democracies have long been accused of mendacity ("double standards") and concealed colonialism. The Indian writer Arundhati Roy criticized at the International Literature Festival in Berlin in 2009 that it is often “precisely the large, democratic nations that – hidden behind the mask of the guardian of morality and in the habitus of the savior of humanity – support and strengthen military dictatorships and totalitarian regimes.” The “robbery of language” she argues, proves to be a “cornerstone of the attempt to turn things upside down” therein (Berliner Zeitung 2009: 35).

When the Sars-CoV2 virus (Covid19) swept across the world from China in 2020, it represented an unusual crisis, particularly so for the democracies in Europe, which are accustomed to the technical controllability of all major problems. This perception of crisis and the accompanying societal stress have evoked an intensified security discourse in this context. With regard to fear as a social problem, processes of securitization cannot, therefore, be disregarded. Security in this dimension is not to be understood in the narrow sense of military security, but requires a broader approach (Buzan et al. 1998). The form this security discourse takes further depends on historical and cultural patterns that have emerged and on how dominant a role fear and risk control have taken up in a society prior to the crisis (compare Beck 1986). The call to put aside particular interests and close ranks, which is regularly expressed during times of crises, is an atavistic attempt to establish security, while the call to strengthen the executive branch is a modern system-functional variant of it. This necessarily goes hand in hand with a reduced influence of the legislature – as was also the case in 2020.

In contrast to authoritarian regimes, liberal democracies in crisis mode tend to run into a dilemma when enforcing coercive measures. Instead of the police and military, two means lend themselves to motivate citizens to behave in a compliant manner. One means of controlling societies without direct force is fear. Fear undermines liberal democracy for at least two reasons. Fear disenfranchises citizens by making them compliant and allowing for any remedy offered by the discursive center to be experienced as being without alternative. Fear provokes the restriction of basic democratic rights and, above all, tends to be blind people for the degree of necessary measures, following a credo that it may be “better to do a little more to be safe.” Moreover, fear can generate its own dynamics in society, which may be difficult to control in the further course of events.

The second means is persuasion. In the force field of an understanding of democracy inherited from the European Enlightenment, persuasion takes the form of an appeal to the insight of the responsible citizen. A morally stabilized consensus may sustain a society if it has come about under conditions of voluntariness in long-term processes of rapprochement between the conflicting groups in society. Under conditions of coercion and crisis, however, morally prescriptive norms develop the potency to discredit persons in an inquisitorial way and to exclude them as enemies. The morally based formulation of enemies can be understood as an extreme case of othering (see also Schönhuth 2005: 172f). While the processes of “othering” range from the harmless “narcissism of minor differences” (Freud) to the sweeping construction of a “national character,” othering turns into the construction of an enemy in the absolute sense when moralizing discredits a person as a whole (on moralizing see Mouffe 2007: 12). Moral pressure can also degenerate into paternalism which – by not respecting citizens as autonomous decision-makers – also runs contrary to the basic principles of liberal democracy. It is at this point that the ruling technique of nudging gains relevance.

This is a starting constellation for the war of citizens against each other. This figure of thought, which constructs persons who do not support the measures aimed at controlling the virus as prescribed by the government as threatening the community and, to that extent, as located outside of it, pervaded public debate and is currently recurring in the dispute over vaccination and vaccination opponents.

On 21 March 2020, 47 dead with 20,000 infected (0.025% of the Federal Republic of Germany population) were reported (see Tab.1). On 26 June 2020 “rbb-InfoRadio", the ARD news radio of Berlin, reported, according to the latest “trend in Germany” that only ¼ of all German citizens felt threatened by Covid-19 at that point anymore. However, the radio spokesman assured in the same breath that the disease is “still deadly”.

The low level of affectedness of the population is also reflected in the development of infections in 2020, where “infection” was not synonymous with “disease” (Fig.2: Infections with Covid19 compared to the previous day). The “first wave” peaked at approximately 6100 infections per day in the first days of April. The mask requirement in public transport was introduced long after, on April 27, 2020, when new infections were already declining and transitioning to a summer low between late April and late September.

“To achieve the desired shock effect, the concrete effects of endemic contagion on human society must be made clear:

1) Many seriously ill people are brought to the hospital by their relatives, but are turned away, and die agonizingly struggling for air at home. Suffocation or not getting enough air is a primal fear for every human being. [...]

2) [...] Children will easily become infected, even with curfews, [...]. If they then infect their parents, and one of them dies in agony at home, and they feel they are to blame [...], it is the most horrible thing a child could ever experience.

3) [...] Even apparently cured people after a mild course of illness can apparently experience relapses at any time, which then end quite suddenly fatally [...]. These may be isolated cases, but will constantly hover like a sword of Damocles over those who were once infected. A much more common consequence is [...] persistent fatigue and reduced lung capacity [...]”.

From mid-March onward – the number of PCR-test-positive cases increased rapidly – reporting in the Berlin media shifted from dispassionate renditions of the overall disease situation to linking Covid-19 with intensive care unit occupancy and death.

6 Images from Bergamo also played an important role in mid-March, creating the impression that so many people had died from Covid-19 that the mass of bodies had to be transported away by army trucks.

7A Case of Othering at “nebenan.de” (neighborhood online communication tool)

The manner in which fear and moral banning contribute to the formation of opposing groups and weaken democracy shall be presented here in a detailed case study based on the analysis of a sequence of postings on the topic of mask-wearing that took place on the platform NEBENAN.DE over eight days (July 30 to August 6, 2020). NEBENAN.DE, now part of the Hubert Burda Media Group, was founded in 2014 by young entrepreneurs aiming that “neighbors could get to know each other, support each other and exchange ideas on topics that affect their neighborhood” (nebenan.de 2021). At the height of the “first wave", when many doctors advised against wearing masks, initiatives were formed by women who sewed so-called “everyday masks” at home and sold them privately, e.g. via NEBENAN.DE. As outlined in the Covid-19-related guidelines for comments, the platform operators prohibit, besides the “dissemination of false news and conspiracy theories” also “posts that deny the Covid-19 pandemic or downplay its extent and consequences” as well as “posts that disseminate statements about measures to deal with Covid-19 that have not been officially confirmed”. The operators explicitly joined the policy of collaboration during the crisis in 2020: “We are convinced that the measures to contain the virus can only have their positive effect if everyone supports them and we support each other during this time” (Nebenan.de 2022).

In this sense, the post on 30 July 2020 in which neighbor person P1

8 appealed “Covid-19: please be careful” was undoubtedly not objectionable. P1 was agitated by the fact that in the local bank branch, where according to regulations only two customers were allowed to be present at any one time, significantly more people were regularly present. P1 therefore made the following drastic appeal to the neighborhood:

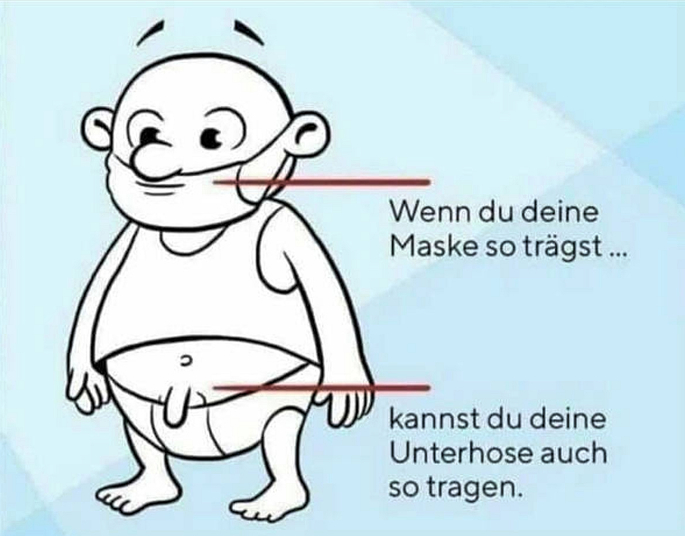

“People, this ‘whatever’ attitude and behavior is simply selfish and inconsiderate! The same applies to the non-wearing of masks in stores and public transport or the oh so cool “partial-wearing", which seems to be especially a fad of men. But honestly: If you let your trunk hang over your mask, it doesn't look super cool, it just looks stupid! We can't afford another lockdown like the one in spring. So please keep some discipline, even if it is hard.”

This opened a thread in which 22 people, mainly women, actively participated until the end. Most of them commented between one and three times during the eight days, but four people (P1, P8, P12 and P13) did so much more frequently, between 10 and 32 times.

Fig.3: post 8 by person P8 (30.7.2020)

On August 30, the editorial staff of NEBENAN.DE apparently closed the comment section “because the contribution and comment guidelines or our rules of polite behavior were not adhered to in the discussion.” Several checks showed that after August 30, changes were still made to the thread; in particular, the posts of neighboring person P13, who was the only one who had consistently expressed criticism of masks and mistrust of media reporting, were missing. In later calls, the note “This comment has been deleted” showed to be replaced by the note “Reply has been deleted by the author him/herself”.

Following the opening post by person P1, which – according to person P12 on 5 August – had

“set off a real avalanche”,

was immediately followed by eight approvals. The eighth post consisted – without words – of a cartoon (Fig.3).

This digital debate which lasted several days held multiple layers of meaning, including a vulgar anti-chauvinism. Another layer is a sweeping, almost culturally critical lament about a general breakdown of order, as in posting No.10:

“There are too many people in our present society who label you “good example” as stupid. According to the credo, it is their own fault if people adhere to rules. Unfortunately, to be witnessed in all public areas.”

Coupled with the expressed conviction to be part of the “good guys", the feeling of being a victim in a threatening world was also formulated in this context. Notwithstanding the circumstance that aerosol researchers classify the likelihood of infections outdoors as vanishingly small (Gesellschaft für Aerosolforschung 2021: 5), the initiators complained that not a lot of distance was kept on sidewalks anymore. They perceived themselves as victims of physical and verbal altercations when admonishing people. “It makes me so angry” (P10, post 14). “The other day on the tram the confrontation almost became physical” (P9, post 17).

On 2 August 2020, P8 (post 67) posted a press note on Dunja Hayali, who had reported about the demonstrators as a “dangerous mixture”. Both the mood of a pre-theoretical everyday feminism, cultural criticism and the perception of victimhood are used here as justification for verbal aggression (hate speech).

“Hate speech automatically leads to hostility”

as P17 (post 56) recognized. Person P12 used (30 July) phrases like

“the ignoramuses’ mindset”, “this ruthless behavior”, “stupid” (post 16).

On 1 August 2020 she spoke of

“brainless idiots” (post 42).

That was the day on which SPD party leader, Saskia Esken, coined the designation “covidiots” for the participants of an authorized anti-government demonstration against the Covid-19 measures in Berlin (Rennefanz 2020: 1). This, thereby somewhat politically approved hateful language met with rejection from some chat participants, however.

“Please let's not tear ourselves apart. [...] Unfortunately, we can only give a good example and address people in a friendly way to convince them of a responsible and conscious way of living together” (P19, post 57).

This type of language, consisting of “accusations and hostility”, criticized person 17 (post 31) as counterproductive. The alternatives offered by P17, meanwhile, were not any more kind:

“incorrigible people”, “deluded persons”, “outdated”

and: Some people needed to be

“taken by the hand a little”.

9Those, however, who really demanded for moderate type of language came under suspicion themselves. A person who had entered the chat as No.12 and who consistently attracted attention with radicalizing statements countered sarcastically (P12, post 59, 2.8.2020):

“The people who bustle about on the anti demos and otherwise also ignore keeping their distance and the face-mask obligations...to point out their misconduct to them in a friendly manner is futile....one has already tried this too often and was only insulted vulgarly and spat at.... [...] ...you are right....these people simply deserve “kindness, understanding and consideration”....this attitude is just unbelievable”

When person P20 then opted out of the chat because she saw too much

“sense of mission”

there, she was also attacked (P8 post 63-64).

Fear and death: the construction of an enemy

The chat had been opened by people articulating their feelings of threat caused by the behavior of others. Should one “address” those persons? The person who had started the thread (P1) advocated for it – “even if it means first having to listen to stupid remarks” (post 12, 7/30). P9 decided:

“I'm not fighting to resolve this anymore” (post 17).

P8, the person with the most numerous comments, called for

“courage and civic courage”: “In any case, I won't let myself be muzzled despite fear” (post 19).

Taking up the keyword “fear", the person who would become the figure of an enemy in the ensuing debate entered the debate with the following post (P13). In post 20, (which was listed as deleted on 28 November), she recommended to read the book “Corona – a False Alarm” by Prof. Reiss/Prof. Bhakdi as “very informative and helpful against fears of all kinds”. In response, individual P8 made the connection of Covid-19 with death, which had also dominated media coverage since March/April. She presented a graph of rising death rates as of 1 April and wrote:

“Every death is one too many.”

To which P13 replied:

“Yes, but life just is not infinite. Two years ago there were 25.900 flu deaths. Were there any “special broadcasts” about it at ARD, ZDF and Co? Did anyone cancel their wedding or miss a concert because of it? I consider sobriety in the assessment of a situation to be very advantageous.”

Thereupon P8:

“25,900 compared to almost 700,000 dead is a small but fine difference in my personal opinion.”

With her astonished inquiry, where this number “700,000 dead” was taken from, P13 got caught on 1 August (post 45) in the indignation of the chat participants over the large demonstration against the governmental Covid-19 containment measures in Berlin. P8 quoted ZEIT-ONLINE (post 33):

“Covid-19 opponents and deniers demonstrate in Berlin against the restrictions. Many are standing close together not wearing masks.”

and followed up (post 35) with the question:

“Why is the demonstration not broken up if the restrictions are not adhered to!”

– a cue for P12, who replied (post 36, Aug. 1):

“[...] on the other hand, today generally, ‘specially such things like demos, which get out of control.... are handled much too laxly and the demonstrators ready to use violence know that exactly....sb. will be arrested from time to time...but one hundred percent he’ll walk out again, happily whistling the next day....naturally without any consequences. this is unfortunately daily routine in Berlin today”

Consequently, several participants questioned the right to demonstrate and called for the state to take drastic action. Using the argument of health hazards, the Berlin Senate did indeed ban demonstrations by opponents of governmental policy on several occasions.

By relativizing the numbers of deaths reported in news broadcasts and newspapers, P13 struck a chord with the narrative built on fear. In post 72, she added:

“Even without Corona, just under a million people die in Germany every year.”

She meant to point out the low average risk of death associated with Covid-19. In fact, in the five months from March to July 2020, just under 9,200 people had died in Germany from or with the virus

10; i.e., about as many as in 3-4 days of a normal year.

11 Citing

correctiv.org12 it was countered that comparing the number of flu deaths to Covid-19 deaths was inadmissible (post 24); others echoed the warning against infectious disease epidemiologist Bhakdi voiced by correctiv.org (P14 and P16, post 24, 30). P12 labeled P13 as a “relativizing person” and an “opponent” and accused this group of people of blindness to reality:

“...maybe these “opponents” should inform themselves properly about what it means for many to get covid-19....would surely be helpful... and not just believe a parrot what some “weirdo” brazenly says... [...] if someone from your ranks....family ..friends...falls ill with it....then there’ll be a big hello, because they actually have zero knowledge about any of it....”

These rejoinders were spontaneously applauded by several neighbors. To reinforce this, P8 posted an excerpt from DIE ZEIT, according to which the Robert-Koch-Institute (RKI) had “reported 955 new Covid-19 infections within one day” and the head of the RKI feared “a trend reversal": “The reason for this was negligence in adhering to the rules of conduct” (1 Aug., cf. Fig.2). Several responses followed, accusing the demonstrators of endangering the lives of others.

With post 48, P13 initiated a discussion of Sweden's Covid-19 policy that spanned 21 requests to speak (1-2 Aug. 2020). In it, she accused German TV and radio stations of one-sided reporting, called for “questioning who really gets sick, who dies, and from what,” and concluded,

“I stick with it: those who want to have a say should inform themselves properly and not spread any half-baked knowledge.”

This appeal provoked counter-accusations mirroring this demand and distancing the speakers from its content (P8 and P16, 1. and 2.8.):

“Half-baked knowledge all right ;-) :-) stay nice and factual please. In your eyes, it's just half-baked knowledge from everyone in this contribution (except you.) Why? Because we see things differently? [...] honestly: I also find it damn hard to stay calm and factual, because this type of baulking at considering facts is just unbelievable.”

P13 ended this thread by referring to culturally and historically different attitudes towards illness and death. All of the remaining five statements by P13 contained the request to react

“with a sense of proportion”,

not to dramatize, to put numbers into proportion ("logic"). In the last post (70, 4 August) P13 once again expressed support for the virologist Bhakdi and the

“many critics of the RKI recommendations” who were “not heard, deleted or misquoted":

“I will not write any further here, as everything has been said. I find it regrettable how many people around us suffer from fears and hardly dare to deal with people in a natural way anymore. I still maintain that reading, learning and forming one's own judgment is the best remedy against this. For this, one must read books and preferably enjoy the media with caution.”

This was acknowledged ironically (P8, post 91):

“A book what is that ???. – There is apparently only one correct opinion to the topic, namely yours. If one sees the thing differently, one is according to your opinion – automatically unknowledgeable; uneducated/stupid; uninformed. You have expressed this several times here by now. Nice”

The question posed by P13 concerning the source of the number of 700,000 dead remained unanswered in the end. But P12, one of the three main speakers, protested against the “pushing around of numbers” (post 76):

“I have to interfere again.....what is the point of the numbers being pushed back and forth.....completely unnecessary....really important fact is.....there is this virus....the fact is also....an unbelievably high number of people have been infected....and very very many die from it...why does it have to be offset against each other now, [...]”

And further jumped to the aid of person P8: “[...] just don't get upset....you were so right” (post 77).

In the last eleven posts of this debate, the most involved persons P1, P8 and P12 exchanged only keywords amongst each other. In the last post (6 August 2020), P8 announced anxiously:

“Covid-deniers want to demonstrate again on 29 August 20 in Berlin :-O”.

On the psychology of we-groups

After only one person, P13, had urged for “sobriety in assessing” the situation (post 22), person P8 already observed (post 25, 7/30):

“On this topic, there are clearly 2 camps here on the platform, and in general, you’ll never reach to a common denominator.”

P8 counted herself and the twelve other people who had expressed similar opinions up to that point in time as belonging to a group that will be referred to here as the “affirmatives”. The multi-member group of affirmatives included the three spokespersons P1, P8 and P12 and other persons who later spoke up and either joined the group in terms

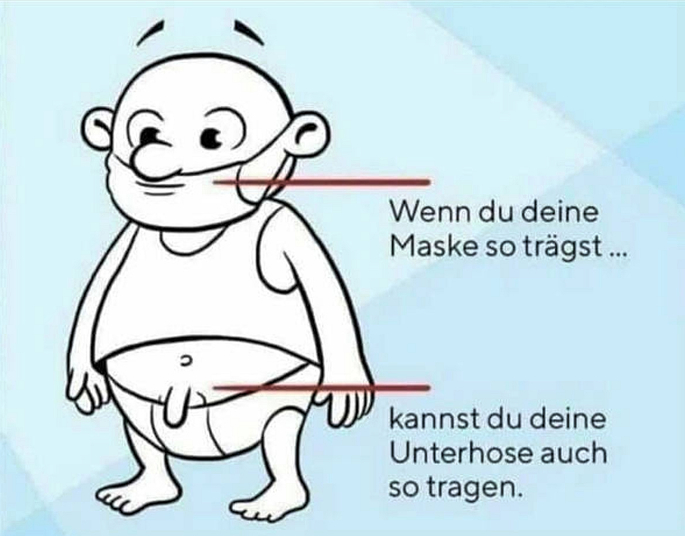

Fig.4: “This caricature from the USA fits the demo today.” (P18 post 38)

of their opinion themselves or were identified in this way by others. It will therefore be addressed as an “we-group” (see for example: Elwert 2001: 245-263; Triebel 2018: 16-20). The persons in this group referred to each other, encouraged each other and perceived themselves, “ethnocentrically", as being correct and on the “right” side. They constructed the group of “others” in the manner exhibited by a caricature that person P18 offered on 1 August:

“This caricature from the USA fits the demo today.” (Fig.4).

This contribution was commented appreciatively:

“Wow [...] that’s great ... fits perfectly” (P8).

In the chat, the dissident person P13 was essentially added to a second group, the “covid ignoramuses” (P12, post 55),

“people who bustle about on the anti demos and otherwise also ignore the distance and the mask obligation” (P12, post 59, cf. “corona skeptics” at P1, post 89).

P1 finally added (post 94) the suspicion that the dissident person in the chat adhered to “conspiracy theories", which had become a dominant talking-point in public opinion particularly during the second half 2020, and added the catchword “Lying press” (Lügenpresse) creating an association context with the AfD:

13“Apparently you are of the opinion that the RKI spreads false information on behalf of the state so that the people .... yes, actually what? And these sinister machinations are not exposed by any party or mass media? – Oh yes, I know: They’re all in cahoots, “lying press” etc. pp. But what exactly is the sinister plan behind it supposed to be?”

The asymmetry is striking. The affirmative group perceived itself as a consistent group, possessed a symptomatic stereotype that was attributed to the opposing group of dissidents, and a clear stereotype of itself that can be described as “reasonableness", “consideration", “care” and a “sense of responsibility.” But what did the stereotype of “the others” look like? In the chat, it is not possible to speak of an opposing group in the literal sense, because there were only a few people with explicitly “dissident” opinions and only P13 in an exposed position. The latter, however, also referred to “facts", figures, logic and reason. The stereotype which P13 expressed, assigned fear, superficial judgment, and the rash handling of numbers to the affirmatives. The profile of those who the affirmatives constructed as their opponents, however, has been clear-cut: they are “deluded", self-centered (cf. Fig.4), irresponsible ("You are not only playing with your own lives, but with ours as well": P19, post 57), “brown-shirt followers” (P19, post 80), conspiracy theorists (P12, post 55).

While the group of dissidents and critics of government measures was generally constructed as homogeneous in everyday discourse and in the leading media in 2020 and 2021 ("Covid deniers,” “conspiracy theorists"), a rather heterogeneous spectrum of perspectives and self-identifications and -representations can be found within various critical groups. In this context, a process of group formation along with a sense of belonging and a homogenous self-image had not yet taken place.

14The analysis of communication in the neighborhood network NEBENAN.DE yields a sobering insight: agreement between different we-groups that stand in exclusionary enmity to one another is difficult to establish communicatively, because in the two strands of discourse the different semantics of basic concepts such as fear, reason, and solidarity thwart translation (compare Rancière 2002). Where one perceives “fear-mongering,” the other perceives “reasonable caution”. The we-groups perform different language games (Wittgenstein 1971). Submitting to the orders of the authorities, especially to wear a face-mask, has been termed “reasonable” in the affirmative group. Those who argued against the wearing of face-masks were dismissed as “unreasonable” in the public service media and newspapers. In post 87 on 3 August, person P8 reproduced a text from the weekly newspaper DIE ZEIT in which a fictitious “educated person” strongly advises to wear a face-mask. In this text, the divergent interpretations of reality are sharply contrasted. He “does not live in fear"; he “only wants to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.” When he wears the mask, he further states that he doesn't “feel like the government is controlling me. I feel like I can contribute something to society as an adult.” Wearing a mask, he says, is not a restriction of freedom, but “consideration.” The text ends with the sentence “Wearing face-masks is not political. It is an expression of common sense in these difficult times!” By continuing with: “just imagine someone close to you – a child, a father [...] plugged into a ventilator and still suffocating, [...].” the text, at the same time, invokes the very fears that the aforementioned paper authored by the Ministry of Interior Affairs (Ministery of the Interior 2020) recommended to spread.

In the chat at NEBENAN.DE, critics also tried to appeal to

“sober reason” and “sense of proportion” to counter behavior they perceived as “panic and overreaction” (P13 in post 22 and 82).

Their accusation of irrationality was directed at those for whom conformity to government actions was simply “reasonable” – such as person P22, who, referring to a news text on N-TV ("The number of people infected with Covid-19 is rising at an unfathomable rate") on 3 August, demanded

“that as an entire society we remain rational.”

Both parties accused each other of holding only “superficial knowledge” (post 86, but fig.2 on this).

Destabilization through the construction of enemy groups

Enmity becomes total when the difference between groups is moralized in such a way that it encloses the human being in its totality. The article in the newspaper DIE ZEIT assigns guilt. Whoever does not wear a mask is to blame for the death of the one who “suffocates, alone without you or a family member allowed at their bedside.” The person who, out of “irresponsibility", that is, a lack that constitutes the person him/herself, is to blame for the death of others, is constructed as the absolute enemy. In post 41 on 1 August, person P8 stated that anyone who joins a demonstration

“recklessly today without distancing and face-mask”

is putting the lives of others at risk tomorrow.

“To me this even borders on assault Sorry.”

Berlin senator of health, Dilek Kalayci, drew the consequence of this complete exclusion in November 2021, when she recommended to stop private contacts with the unvaccinated (BILD 2021: 11).

In 2020, the attempt to create a national community through a rhetoric of commonality and solidarity caused the German population to split into two groups. The chat at NEBENAN.DE is a reflection of this. At least one of these groups can rightly be considered a “we-group” because it was portrayed as one group by the leading media, press, radio and television, and positively characterized as the “reasonable ones”. It also identified itself in this way. As a counterpart, a group emerged that was inevitably constructed as the “unreasonable” and community-damaging one (see Triebel 2020: 4-7). The face-mask has been the vehicle of this division into good and evil.

After the Corona crisis, we suspect that democracies can perish not only through elected tribunes of the people revising democratic institutions over time. It is also possible, as observed in the NEBENAN.DE thread, that democracies undermine their own basis of communication through multiple forms of dividing language; through tactically employed fear that does not take citizens seriously as mature persons whose judgment is to be trusted; through appeals to “reason” that in reality contain the threat of coercion or communicative exclusion. Dietrich Brüggemann (campaign “#ALLESDICHTMACHEN") (Brüggemann 2021: 16) has argued that beating down of demonstrators, intimidation of doctors, searching the homes of judges who have authored sentences against masks – all this should not be allowed to happen in an open, free and liberal society. “A culture that acts in this way multiplies its enemies” (ibid.).

Despite all the rhetoric of solidarity, hostility and enmity remain realities of the social world. More differentiated research is needed to help uncover the manner in which hostility and enmity are involved in the genesis of we-groups and under what circumstances they may destabilize societies. Difference and freedom are basic elements of Western pluralistic democracies. The “Covid-19 crisis” has revealed that the appreciation of the freedom of the individual is not so stably anchored in Western democracies that this basic democratic value of democracy would be held on to even in times of crises. It is especially in times of crises that difference tends to be perceived as dangerous. To what extent this is really the case, however, is anything but resolved. If difference, deviant opinion or behavior, is a constant cause of fear for authoritarian systems, fear is their omnipresent means of rule. With the paralysis of a discourse free of fear during the Covid-19 crisis, the credibility of Western democracy has also entered into a crisis. The connection between fear and freedom has not been sufficiently dealt with either empirically or philosophically. Fear calls for security. The discourse of security, which takes place in the politics of decision-makers and in the everyday lives of citizens, must be examined for the threats it poses to democracy. Both with regard to internal systemic crises and with a view to an intercultural competition between political systems, Western democracies have to engage with and clarify for themselves the relationship between freedom and security that is constitutive for them.

In 2020 the interest for George Orwell’s writing increased again. His novel “1984” was pusblished in a revised translation in 2021 at dtv. The publisher advertised the book arguing it was more relevant currently than ever! The official language used in describing Covid from 2020 onward is deserving of an analysis in itself. Concepts such as “reason”, “responsibility”, and “solidarity” gained new levels of meaning. Linguistic articulations contained strategic infantilization such as the little “prick” to refer to an intervention into rights of personal freedom that need to be legitimated with regard to the Constitution. Beyond this, dominant media outlets aimed at introducing administrative use of language as binding, for example „fastened authorization” instead of “emergency authorization”, “obligation for vaccination” instead of “compulsory vaccination”. In instances which referred to regulations, requirements and provisions, dominant media outlets consistently spoke of „rules“, concealing their binding nature and introducing a playful tone to these issues. The term face-mask was regularly avoided and whenever possible, replaced by the term “mouth and nose protection” or “mouth and nose cover”.

Following the meaning of a system of rules, norms and principles. See fore example Zürn, 2002.

See for example the discussion on the fourth international strategic conference of the Austrian Defense Academy, Vienna which debated the topic “thinking strategy in a novel fashion – democracy and strategic ability”, June 2021.

During the 18th legislative period 2013-2017 three consultants on “behavioral economic” joined the staff of the office of the chancellor. See: Dams et al. 2015

See Ministry of the Interior 2020. “Wie wir COVID-19 unter Kontrolle bekommen” [How we will get Covid-19 under control]. The paper was also made available at: (https://fragdenstaat.de/blog/2020/04/01/strategiepapier-des-innenministeriums-corona-szenarien/) and was later also published by the federal government (accessed 2 October 2020, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/2020/corona/szenarienpapier-covid19.pdf;jsessionid=F11B42F8DF30BE19D201AD7FF323BD2C.1_cid364?__blob=publicationFile&v=6). The identity of the authors has not been officially been made public. They were German economic and social scientists. According to the Aargauer Zeitung an admirer of the People’s Republic of China was amongst them (Bernet 2021). According to documents available to the author, the sociologist Heinz Bude, whose book “Solidarität – Die Zukunft einer großen Idee” [Solidarity – the future of a great idea] was published in the previous year, was also part of the working group. He has so far not reacted to several requests for information regarding this issue (for a review see Niedlich 2019).

The dramatic online dossiers authored by the business economist, manager and IT-technician, Tomas Pueyo, are likely to have paved the way for the legislative – especially so his contribution “The Hammer and the Dance” (Pueyo 2020).

As has become known by now, this has been a false impression (compare Metzdorf 2021).

For the purpose of anonymization, the participants are identified via numbers. These are according to the sequence in which they joined the chat. The wording of citations has not been altered.

It follows that critics are here being presented as somewhat immature persons, as expressed by the term “stick-in-the-mud” which has been used during the first half of 2020 in order to reproach people for not wearing facs-masks (compare Szymanski in this issue). The aspect of public infantilization should be investigated further.

Confirmed cases of death according to the Robert-Koch-Instituts (RKI) from 9 March until 30 July 2020 amounted to 9.134. Made available on Wikipedia (Wikipedia 2020). It remains unclear at this stage, whether these cases of death were caused by Covid-19 directly. Within the statistical data, persons were also registered as cases of Covid-19 death if they were admitted to hospital with symptoms unrelated to Covid-19 but also had a positive Covid-19 test result, according to the DIVI-Intensivregister. (Barz 2021: minute 45:24). Around this film, on a day at the end of August, there were clashes with similar positions of confrontation on the platform NEBENAN.DE.

The average number of cases of death in Germany per day since 2010 amounts to approximately 2500 (Statista 2022).

Correctiv.org is the publishing arm of a limited liability company located in Essen which undertakes fact-checks. Besides donations the company also receives state-based support (see Meyen 2021: 99, fn. 25).

“Alternative für Deutschland”, a right-wing political party.

A first step in this direction may have been formulated in A Letter on Justice and Open Debate (2020). Spontaneous associations such as “Wir2020” [„We 2020“] and “Widerstand2020” [“Resistance2020”] quickly dissolved again.

Bibliography

-

A Letter on Justice and Open Debate (7 July 2020). In: Harper’s Magazine. https://harpers.org/a-letter-on-justice-and-open-debate/

-

Albright, Madeleine (2018). Faschismus. Eine Warnung, Köln: DuMont.

-

Roy, Arundhati (2009). Das schwindende Licht der Demokratie. In: Berliner Zeitung (10 Sept. 2009).

-

Barz, Marcel (2021). Die Pandemie in den Rohdaten. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nEPiOEkkWzg

-

Beck, Ulrich (1986). Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

-

Berlin, Isaiah (1969). Two Concepts of Liberty, in: Four Essays On Liberty. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

-

Bernet, Christopf (22 Feb. 2021). Wie ein Germanistik-Doktorand und Mao-Bewunderer aus Lausanne zum Corona-Berater der deutschen Regierung wurde. In: Aargauer Zeitung. https://www.aargauerzeitung.ch/schweiz/schockwirkung-erzielen-wie-ein-germanistik-doktorand-und-mao-bewunderer-aus-lausanne-zum-corona-berater-der-deutschen-regierung-wurde-ld.2105084

-

BICC Bonn International Center for Conversion / HSFK Leibniz-Institut Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung / IFSH Institut für Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik an der Universität Hamburg / INEF Institut für Entwicklung und Frieden. (2021). Europa kann mehr! Friedensgutachten. Bielefeld: transcript.

-

Brüggemann, Dietrich (23 August 2021). Sagt Eure Meinung, schwimmt nicht mit dem Strom – Interview mit Michael Maier. In: Berliner Zeitung.

-

Buzan, Barry/Wæver, Ole/de Wilde, Jaap (1998). Security. A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

-

Crouch, Colin (2008), Post-Demokratie, Berlin: Suhrkamp.

-

Dams, Jan/Ettel, Anja/Greive, Martin/Zschäpitz, Holger (2015). Merkel will die Deutschen durch Nudging erziehen. In: DIE WELT. https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article 138326984/Merkel-will-die-Deutschen-durch-Nudging-erziehen.html (12 March 2015).

-

Elwert, Georg (2001). Ethnizität und Nation. In: Hans Joas/ Steffen Mau (eds.). Lehrbuch der Soziologie. Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus

-

Geiselberger, Heinrich (2017). Die große Regression. Eine internationale Debatte über die geistige Situation der Zeit (eds.). Berlin: suhrkamp.

-

Gesellschaft für Aerosolforschung (2021). Positionspapier zum Verständnis der Rolle von Aerosolpartikeln beim SARS-CoV-2 Infektionsgeschehen.

-

Hentges, Gudrun (2020), Krise der Demokratie – Demokratie in der Krise? Gesellschaftsdiagnosen und Herausforderungen für die politische Bildung (eds.). Frankfurt: Wochenschau.

-

Hirschmann, Kai (2017). Der Aufstieg des Nationalpopulismus. Wie westliche Gesellschaften polarisiert werden. Berlin: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

-

Levitsky, Steven/Ziblatt, Daniel (2018). How Democracies Die. New York: Crown

-

Metzdorf, Julie (26 October 2021). Der Militärkonvoi aus Bergamo — Wie eine Foto-Legende entsteht. In: KulturBühne. https://www.br.de/kultur/wieso-das-foto-des-militaerkonvois-in-bergamo-fuer-corona-steht-100.html

-

Meyen, Michael (2021). Die Propaganda-Matrix. Der Kampf für freie Medien entscheidet über unsere Zukunft. München: Rubikon.

-

Mouffe, Chantal (2007). Über das Politische. Wider die kosmopolitische Illusion, Frankfurt a. Main: suhrkamp.

-

Nebenan.de (19 Feb. 2021). Richtlinie für Corona-Beiträge bei nebenan.de. https://hilfe.nebenan.de/hc/de/articles/360017500600-Richtlinie-Corona-Beiträge-bei-nebenan-de.

-

Nebenan.de (23 May 2022). Richtlinie für Corona-Beiträge bei nebenan.de. https://hilfe.nebenan.de/hc/de/articles/360017500600-Richtlinie-f%C3%BCr-Corona-Beitr%C3%A4ge-bei-nebenan-de.

-

Niedlich, Ferdinand (2019). Heinz Bude – Solidarität: Die Zukunft einer großen Idee, in: SSIP–IKA 61(1-2).

-

Pueyo, Thomas (2020). Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance

-

Rancière, Jacques (2002). Das Unvernehmen. Politik und Philosophie. Frankfurt a. Main: edition suhrkamp.

-

Rennefanz, Sabine. Ja, dürfen die das? In: Berliner Zeitung (3. August 2020).

-

Schönhuth, Michael (2005). Glossar Kultur und Entwicklung. Ein Vademecum durch den Kulturdschungel. In: Trierer Materialien zur Ethnologie 4. Trier: Universität.

-

Statista (2022). Anzahl der Sterbefälle in Deutschland von 1991 bis 2021. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/156902/umfrage/sterbefaelle-in-deutschland/.

-

Triebel, Armin (2018). Durchlässige Grenzen. Bemerkungen zum widerspruchsvollen Zusammenhang von Homogenität und Grenze. In: Drea Fröchtling/Roswith Gerloff/Armin Triebel (eds.). Glaube über Grenzen hinweg/Faith Across Frontiers. Series: Perspektivenwechsel Interkulturell (6). Berlin.

-

Triebel, Armin (2020). Polarisierung bei Wir-Gruppen ist unausweichlich. In: SSIP-IKA 62(1-2).

-

What the Next 18 Months Can Look Like, if Leaders Buy Us Time. https://tomaspueyo.medium.com/coronavirus-the-hammer-and-the-dance-be9337092b56.

-

Wikipedia (2020). COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland/Statistik/2020. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19-Pandemie_in_Deutschland/Statistik/2020#Infektionsf%C3%A4lle.

-

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1971 [1953]. Philosophische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt a. Main: suhrkamp.

-

Zürn, Michael (2002). Lexikon der Politikwissenschaft II. In: Dieter Nohlen/Rainer-Olaf Schultze (eds.) München: beck’sche Reihe.

Kritische Gesellschaftsforschung

Issue #01, July 2022

ISSN: 2751-8922

In this Issue:

Jochen Kirchhoff

Cognition and Delusion. The Problem of Science in the World Crisis

Hannah Broecker

Negotiating the future of political philosophy and practice: Renewal of democracy or technocratic governance

Mark Neocleous

Immunity: Security; Security: Immunity… ad infinitum

Christina Gansel

Communicating Fear in the Corona Pandemic: On the Pattern of a linguistic-communicative Practice

Adam Szymanski

On the Scapegoating of the Unvaccinated: A Media Analysis of Political Propaganda During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Armin Triebel

The Destabilization of Democracies – A Discourse Analysis

Michael Meyen

Why communication studies needs a reboot